In the epilogue of his book Third Class to Dunkirk (1944) my father Peter Hadley reflected on the UK’s lack of preparedness for conflict, and how we need to be vigilant for the future. It seems to me that his words are absolutely relevant to the dangers we face as a country and as a world in 2026; and could apply – mutatis mutandis – as much to the political-cultural sphere as to the military.

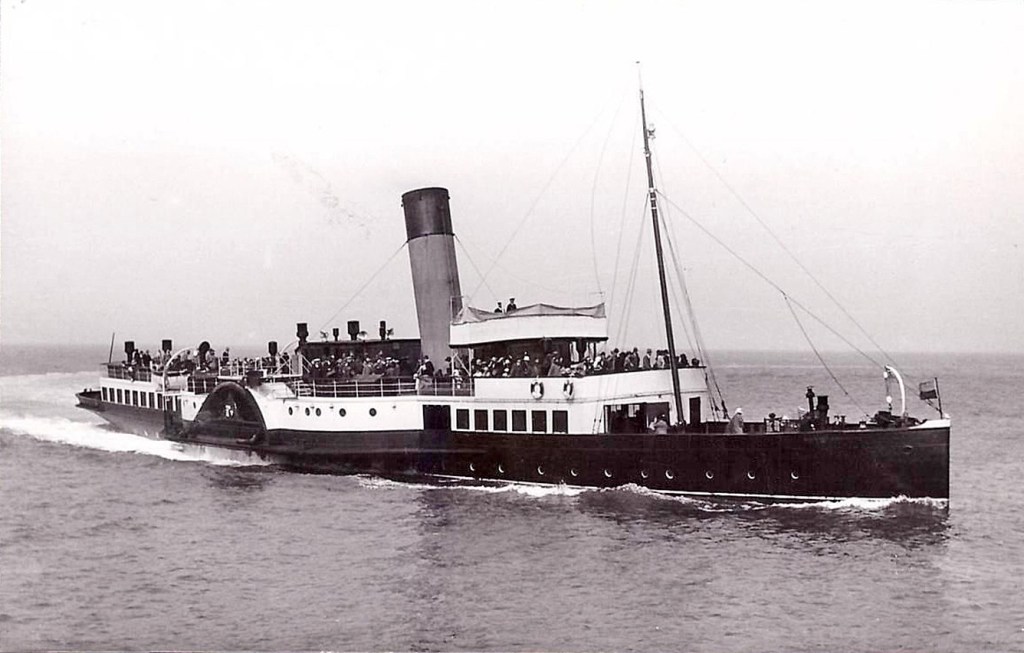

The paddle steamer Duchess of Fife, which evacuated Peter from the beach at Dunkirk.

From Third Class to Dunkirk, by Peter Hadley (Hollis and Carter, 1944)

I feel strongly that it is only by emphasizing and re-emphasizing the lessons of this war that we can hope to avoid a similar catastrophe in the future…

My predominant impression remains the same today [1944] as it was in 1940 – of a hopeless struggle by an un-armoured force, ill-equipped and almost totally lacking in air support, against an enemy overwhelmingly superior in his equipment and methods of warfare. It was our own fault. For years the democracies had continued to whistle in the dark, oblivious to the gravity of the situation, deaf to all but the music of wishful thinkers. “There will be no war – this year or next”, stated the Daily Express in 1939, and the anxiety of the public to be told something which it so desperately wanted to believe was mirrored in the mounting sales of that influential paper… “The best equipped army in the world” was the description applied to the force which landed in France with only a handful of tanks to face the German armoured divisions. No – we have had enough of wishful thinking.

Let us, then, face the fact that we entered the present struggle totally unprepared for modern warfare. It is true that the country, which had done little but stir fitfully in its slumber at the interruptions of Abyssinia, the Rhineland, Austria, and the Spanish Civil War, did crawl reluctantly out of bed at the time of Munich, and finally, with the occupation of Prague, decided that it was time to get dressed. But we had too much leeway to make up… Small wonder that in 1938 we looked back somewhat wistfully on “the years that the locusts have eaten”… The lesson here is clear enough: we must never again allow our own armaments to lapse while other nations are making obvious plans for aggression.

…

Let us learn the most important lesson of all – that a small war now is always preferable to a great war five or ten years hence. If the Western democracies had recognised the truth of that principle, and had had the strength to put it into practice, this misery would not have come upon us. Even a moderately strong Britain and France, recognizing in the reoccupation of the Rhineland the first uneasy stirrings of a homicidal maniac, could have stepped in without difficulty to reinforce his chains. The Austrian Anschluss and the so-called Sudeten crisis were equally obvious forewarnings of what was to come. Why, then, was nothing done? Because the British and French Governments lacked three things: first, the will to action; second, the popular demand for action; and, third, the means of action. The first of these, it has always been presumed, depends on the second; but I submit that this is a fallacy. The task of a government is to act on behalf of its people; and if through blindness or apathy the people are unable to see the danger signal for themselves, or if they lack the opportunity or the inclination to voice their opinions sufficiently strongly – as will often happen – then it is for the Government to give a lead, and if necessary, it must use all its powers of publicity and propaganda to bring the nation round to a realization of its peril.

In particular, let us, when this struggle is over, say less than we did in the nineteen-thirties about the “horrors of war”. That war is bestial and altogether loathsome is undeniable: but to emphasize the fact continually is to induce in oneself and in others an increasing determination that war must be avoided at all costs – in other words, our old friend “peace at any price.” Paradoxically enough, nothing makes war more certain than the adoption of this attitude, for it engenders a policy of appeasement, with all its dangerous consequences. A war postponed is not a war averted: it is a war magnified – it may even be a war lost.

During the Great War a poet wrote – “If ye break faith with us who die…” Those words ran through my head on the day that Germany invaded Poland, and they have recurred obstinately, time and again, ever since. Well – we have broken faith, and, painful though the admission must be to some, those who died in 1914-18 died in vain. Let us make sure of it this time. Let us, by all means, strive to establish a new world order which will eventually render armaments superfluous and war an outcast. But let us in the meantime remain sufficiently prudent, sufficiently sceptical, to retain and maintain, first, a strong armed force ready to fight for the preservation of peace; and, second, the courage and determination to use that force unhesitatingly against any who in the future may dare to put personal or national ambitions before human happiness and international goodwill.